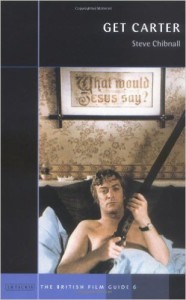

There is no better analysis of the film than the British Film Guide which was written by Steve Chibnall. This book, published in 2003, is now seemingly out of print and was originally published as part of a series written by various authors. It was collated with access and co-operation from Mike Hodges and contains a multitude of information, an analytical scene-by-scene ‘essay style’ breakdown, shooting schedule and a rough, early version of the script. It is simply a must read for any Get Carter fan.

There is no better analysis of the film than the British Film Guide which was written by Steve Chibnall. This book, published in 2003, is now seemingly out of print and was originally published as part of a series written by various authors. It was collated with access and co-operation from Mike Hodges and contains a multitude of information, an analytical scene-by-scene ‘essay style’ breakdown, shooting schedule and a rough, early version of the script. It is simply a must read for any Get Carter fan.

You may find it on the various online auction sites and it does occasionally crop up on Amazon but with it being out of print, it is getting increasingly hard to source. Whilst Amazon doesn’t offer an eBook version of it, Google does, so that may be your best bet to read it.

Buy paperback from Amazon / Buy eBook from Google Play

50 Year Video Essay

To celebrate the 50 year anniversary in 2021, ‘Movie Birthdays’ YouTube channel have put togther a fantastic retrospective of the film. It gives a great 15 minute introduction to the film and it’s place in modern cinemal. Warning – contains spoilers!!

Wikipedia

The article over at Wikipedia is an invaluable and detailed breakdown of the film. I have sourced a number of excerpts from there for this website. All content is replicated under the Wikipedia

Script

Thanks to the wonderful people over at Cinephilia and Beyond, we have access to the original screenplay written by Mike Hodges. An intriguing document that includes all the musical scores contained within the film and all credit sequences listed.

All credit to Cinephilia and Beyond for making this available. Please visit their website for other movie treats.

Trailer

A Critical Evaluation of Get Carter

The following essay gives an excellent introduction and brief analysis of the film. It wasn’t written by me, I have seen it on various websites without any attribution to the author. I’ll post it below, but if you are the author, or know where it originally came from, I’d be happy to credit you – so please get in touch.

“That a film as dark and condemning, as crisp and clever as Get Carter should have been co‑opted by ‘Cool Britannia’ is repellent. Get Carter is not cool, its cold but there is power and intoxication in that coldness and it is in that that the picture finds its own considerable power.”1

In the post‑modern era of Pulp Fiction (1994) and other stylised gangster movies, Get Carter still retains a position of pre‑eminence in the film making communities (almost sacrilegious in some circles) in Britain and America to the extent that the film was re‑released in British cinemas in 1999. Its star, Michael Caine, likewise experienced something of a revival during the 1990’s, for example, his shoot for the cover of GQ magazine in September 1992, which made heavy reference to the watershed role he played in Get Carter.2 The movie was re‑made with Sylvester Stallone in the lead role re‑locating the action to upstate New York in 2002. Unsurprisingly, the American remake did not do very well at the box office and it bowled over few film critics. As we shall see, the reason for this lies predominantly in the specific location and context of the original movie; it is bound in bonds enduringly with the North‑East of England, its quintessential lead actor in the title role and the historical setting of the early 70s.

Rarely has a British film been produced that sits at such a polar opposite to mainstream Hollywood cinema than Get Carter (Mike Hodges, 1971). From the dream‑like opening frame showing Carter looking out from a lofty window to the opening of the credits, filmed with a hand held camera on a rickety intercity train to one of the most northern outreaches of civilised Western Europe (where the eventual killer of the anti‑hero is sat in the same carriage as Carter), Get Carter exudes a break with history, tradition and, more specifically, signals the beginning of an entirely new genre of British gangster movie that sits at odds with its American counterpart and portrays a realism that was hitherto unknown. Throughout this analysis of the movie it should be borne in mind that Get Carter represents much more than a crime caper. It is a social drama, a study of one man’s personal moral battle and spiritual complexity; it is a thriller, a whodunit; above all, it is a tale of family, belonging and betrayal, a potent mixture that has been used since the Classical Era to evoke realism and induce audience empathy and reaction, all within the context of dramas surrounding real people in real locations. Get Carter remains encapsulated in a separate, more soulful era of British movie making that is as divorced from films such as Snatch (2000) as it is from mainstream Hollywood movie making.

Get Carter is based upon Ted Lewis’ novel, Jack’s Return Home about a native of the North East of England who leaves his new base in London to investigate the mysterious death of his brother in his home town. The film took thirty six weeks to make from the moment that Mike Hodges acquired the rights to the novel until the final edit. The total cost of production was three‑quarters of a million US dollars, extremely economical, even in the context of the time period when it was shot. The shoot itself lasted under forty days, which made it tantamount to something of a ‘white heat’ of a film production. It was Hodges’ first feature film and the first occasion that he had worked with a true screen star, which is highly significant in terms of the objectivity of the director, as highlighted by pioneering Hollywood director Gus Van Sant. “The point of any film, big or small, is to make a good one, and then let the scope and subject dictate the expansiveness of the audience. But a lot of the decision making depends on what a person has done before. Opinions about art are so subjective that the only objective orientation becomes your past product.” 3

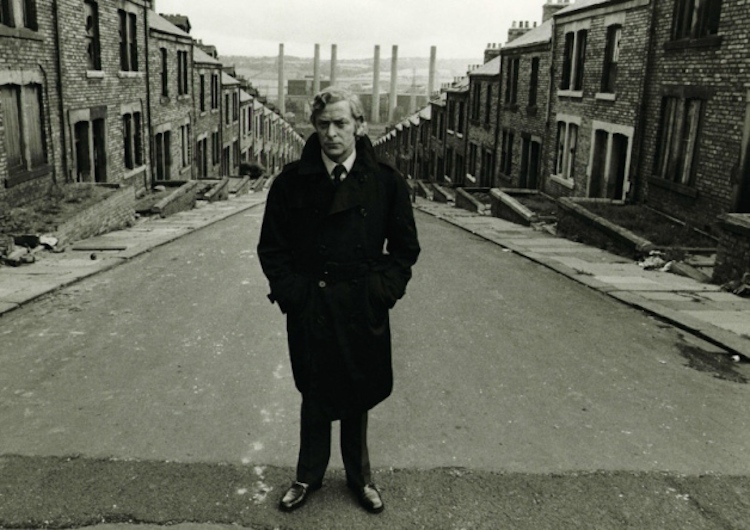

The casting of Michael Caine in the lead role was a masterstroke as he superbly characterises the chasm that existed between the north and south of England, his quintessentially London swagger sitting awkwardly alongside the barren pubs and bookmakers of inner city Newcastle. From the actor’s point of view, Get Carter offered an opportunity for Caine to shed his type‑cast skin by tackling an altogether new part while still playing on the stereotypical Londoner image that he had garnered for himself in films such as Alfie and The Ipcress File. Caine himself felt that the film and the lead role was the most realistic that he had hitherto taken on. “One of the reasons I wanted to do it was because I had this image on the screen as a Cockney ersatz Errol Flyn. The Cockney bit was alright, but the ersatz suggested I’m artificial and the Errol Flyn tag misses the point. One’s appearance distracts people from one’s acting. Carter was real.”4

Almost all contemporary British crime movies up to that point were made in London, involving Londoners, acted by Londoners, with the capital city cast as the physical manifestation of the social and ethnic melting pot of post war Britain. This had as much to do with the desires of the producers to sell the film overseas as it was concerned with the subjugation of the social majority of the population of the UK. “The working class, from the miner to the farm labourer, are tied more closely to the local economy and are marginalised in a commercial film intended for an international market. Most obviously, accents have to be understandable by audiences with no knowledge of slum life or its humour.”5

Although the producers of Get Carter were wary of the issues outlined herein, with particular reference to accents and regionalism, the cast of the film at least contains a healthy proportion of actors from the North East with local actors such as Bernhard Hepton (Thorpe) and Geraldine Moffatt (Glenda) particularly discernible throughout the movie. This meant that the final cut of the film was true to its working class, regional roots, although Hodges admits that he had to edit the opening scene involving Carter’s gangland bosses because the producer (Michael Klinger) felt that the London accents were incomprehensible and the dialogue too colloquial. It was a mistake he vowed never to make again as he felt the edit inevitably took away much of the authenticity of the opening of the film.

Taken as a whole, however, Get Carter is, socially speaking, a revolutionary film for its time. The significance in this sociological shift should not be underestimated. Without the pioneering attitude of the makers of Get Carter it is difficult to imagine highly localised films such as Trainspotting (1997) ever being made. Essentially, Get Carter was a successful experiment in moving British film locations out of the social bubble of London; furthermore, its subsequent position as a gem in the British crime drama genre underscored the value in social and geographical diversity. It thus encouraged film makers from all reaches of the British Isles to consider making a movie about their home town, just as Get Carter paid a somewhat depressing homage to Newcastle‑upon‑Tyne.

Indeed, it is hard to escape the feeling that the city of Newcastle plays as an important a part in the film as does Michael Caine. Its foreboding, narrow Victorian streets appear to constrict around the anti‑hero, trapping him as an unwilling prisoner, which mirrors the game of ‘cat‑and‑mouse’ that characterises Carter’s search for the truth behind his brother’s untimely death. As we view, piecemeal, the degeneration of the city, we see Carter’s descent into an increasingly violent, sadistic and corrupt way of life with a tragically foreseeable conclusion that is prevalent even without the aid of hindsight. The split between the vacuous ‘New Wave’ movies of the sixties and the realism of Get Carter is thus achieved through the medium of the city of Newcastle. At times, especially those scenes filmed in the streets and the dockside, the film has the aura of a documentary, such is the audience’s appreciation of the landscape and the people who inhabit it. It is all part of the manipulation of the camera lens for purely cinematic ends.

“Cinema as a photographic medium instantly poses its images and sounds as recorded phenomena, whose construction occurred in another time and place. Yet though the figures, objects and places represented are absent from the space in which the viewing takes place, they are also (and astoundingly) present.”6

However, the camera lens can only make so much of a difference to the ultimate feel of a picture. Acting, dialogue and plot remain the fundamental elements of film production, in addition to the few films that are made that capture a moment in history, of which Get Carter is a fine modern example.

Get Carter is such an important film because of the way in which it addresses the end of one decade and the beginning of another, incorporating a complete transformation of mood and style that is as startling to a first time viewer today as it would have been upon its release in 1971.

The 1960’s is a decade that has attained quasi‑mystical status in studies of sociology and politics in the UK and indeed throughout western civilisation. In Britain, a feeling of intractability was fostered with the breakdown of traditional social mores incorporating a relaxation of sexual values and, for the first time since 1945, a real sense of a new dawn beginning. In every sense, therefore, the sixties was the most important decade of the twentieth century, specifically in terms of sociological change where an unbridled sense of enthusiasm was given a free reign. Get Carter arrived like a freight train and blew away the mythology surrounding the sixties.

The social and historical background to the filming of Get Carter is essential and the film must be viewed within this rigid context to be fully appreciated because the film highlights, more than any other music or media at the time, the cold realisation that the freedom of the sixties had gone, replaced by an altogether more terrifying and problematic era of deteriorating urban centres and a society in pursuit of the hedonistic goals that characterised and ultimately blighted the previous decade. “The dour Newcastle setting establishes a sense of distance from Swinging London, offering instead a desolate and unsettling backdrop, from which the sense of optimism and excitement associated with the 60s have disappeared.”7 Get Carter represents the end of an epoch in British cinema and the beginning of a more representative form of film making in the UK. “We might assume that a British film presents Britain to itself, and possibly to a foreign audience, in terms of its social and regional uniformity and diversity.”8

Whereas the Ealing comedies in the 1950’s and the ‘New Wave’ films of the 1960’s evoked imagery pertaining to the Victorian era, Get Carter was rooted in its own time. It was not concerned with looking backwards. One can argue that the movie was sometimes prophetic in its vision of the future, particularly in the scene which uses the abandoned multi‑story car park, which can be seen as symptomatic of the urban redevelopment programmes of the later 1970’s. Local businessman Bromby is likewise portrayed as the property tycoon of the future; lots of money but little taste. But, essentially, this is tantamount to over analysis. At the time of production, the cast and crew were concerned only with making a contemporary movie in a real setting.

Get Carter was one of the few films of the decade to stand still and act as a semi‑factual piece of film‑making, exacerbated by its striking cinematography. In terms of style, therefore, Get Carter represented a complete swing in focus from the aesthetic and nostalgic to the realistic, a shift that would have lasting consequences for the gangster and drama genres on both sides of the Atlantic. Indeed, the term ‘realism’ is frequently evoked in any analysis of Get Carter, particularly in reference to the use of location and real looking actors to depict real life situations. Get Carter was one of the first British films to portray the gangster persona in its true light; previously the archetypical British villain was represented as stupid, silly or funny, a parody of itself.

“Realism has been treated with suspicion, its claim to picture things ‘the way they are’ dismissed as an illusion fostered in the interests of ideology. Seen from this perspective, the predominantly urban and industrial landscapes of British film realism and the stories of the mainly working class characters that populate these landscapers are revealed as vehicles for the expression of middle class and patriarchal values.” 9 This was not the case in Get Carter where the director drew upon the lead actor’s own upbringing in Elephant and Castle where Caine was able to pick up on the mannerisms of London’s real life gangsters.

Get Carter marks a discernible shift in the way British film makers would henceforth treat the gangster genre. Hodges and Caine treat the subject with respect and follow intricate details to ensure that the final product is as true to life as possible. A scene such as the one where the camera lingers on a seemingly endless procession of funeral cars following Frank Carter to the crematorium is a classical portrayal of gangster imagery. Attention is likewise paid to the detail of Carter’s dress, his methodical, obsessively neat appearance, predominantly clad in black, reminiscent of the quintessential American gangster movies. The scene, at the beginning of the film, when he unpacks his suitcase, nonchalantly shaves and prepares his firearm is a lesson in objectivity, detail and realism. The notion of family is likewise a classical gangster genre factor, which is used in Get Carter to great effect. Distant, cold and calculating though Jack Carter may be, it is the ultimate truism of the film that he is back in Newcastle to protect the honour of his family, in spite of his own painfully obvious lack of human empathy.

It should be noted that although Get Carter uses humour, in evidence during the scene towards the end of the movie where Carter smirks to himself as two of his victims end up in the Tyne, the film steers clear of the dangerous association between humour and violence that has characterised most of the post Tarantino generation of crime film makers. To what extent Get Carter has influenced this shift in emphasis is open to debate. “For modern audiences, the black humour and triumphant nihilism of Get Carter and The Long Good Friday are probably more significant than their naturalism or moral appropriateness. In any case they have been used not as templates but as resources to be affectionately rummaged through for inspiration and ironic quotation. The result has been not genre purity but a diversity in which professional crime provides a linking motif for a spectrum of films from those that strive for unvarnished authenticity to those that cheerfully peddle myth.” 10

What Get Carter does achieve (in fitting with the film as a whole) is to inject the violence with a sense of realism. For instance, when Carter throws Bromby’s body from the heights of the car park, he does not land on the ground as is often the case in traditional action movies. Instead, Hodges has Bromby crash through the roof of a car containing a mother and her children, highlighting the symbiosis between the world of the gangster and the audience’s comfortable existence. Essentially, what the film makers are saying is that violence has real life consequences. Get Carter is therefore a much more socially conscious film than any of its modern counterparts.

The key to the success of Get Carter is the way in which the movie immediately engages the audience and fosters a relationship with it based upon perception, which, in the first instance, is always the key to the bond between viewer and director. The ultimate vision of the director lies with the viewer: an object of perception is thus presented literally to the eye of the beholder.

One of the central ways in which Get Carter manages to manipulate and control the attention of the audience is via a classical detective narrative. The vacuum created by the lack of any police involvement (beyond them acting as a gullible pawn of the anti‑hero, for instance when he kills Margaret and sets up the crime scene so as to incriminate an entire house‑full of debauched party‑goers) is filled by the viewer. We are taken, step by step, through the narrative. Because Carter never discloses his private thoughts to any of the characters and because Hodges decided not to use the American methodology of asides, the audience is left to form its own conclusion about the core theme of Frank’s murder, in the same ad hoc way in which a detective would try to solve the case. When Jack makes a discovery, so do we. We thus evolve emotionally with the lead character.

“The detective film justifies its gaps and retardations by controlling knowledge, self‑consciousness and communicativeness. The genre aims to create curiosity about past story events (e.g. who killed whom), suspense about upcoming events, and surprise with respect to unexpected disclosures about the story.”11

Director Mike Hodges keeps the audience in the dark for as long as he feels necessary. Human curiosity is the determining factor behind audience participation and it is a fact not lost on the director. He refrains from hinting at the reason behind Jack’s brother’s murder until three‑quarters of the way through the duration of the film. Hitherto, all that the viewer is certain of is that there was serious foul play involved and that Jack’s brother was not, like Jack, a career criminal. It is therefore made implicit that his death contains a more sinister motive than if he had also been a gangster. Certainly, the plot relies on the civilian, hard‑working, proletarian nature of the initial victim for reasons of empathy.

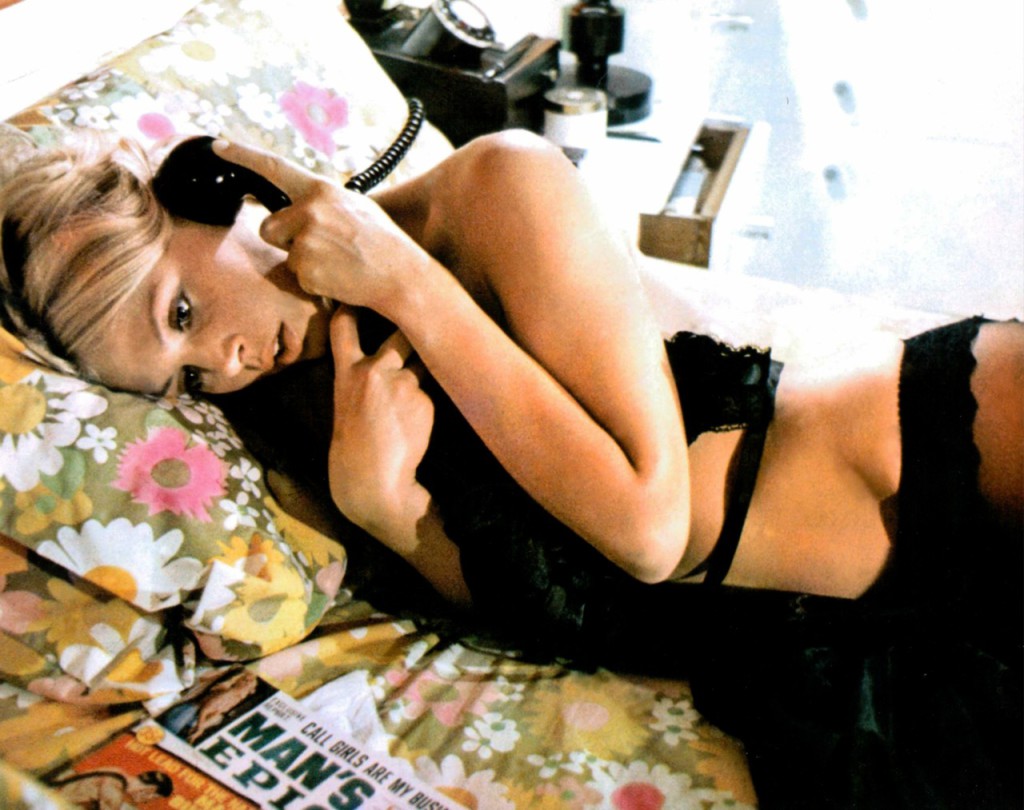

Suddenly, in a riveting scene involving Jack and Glenda the director introduces an intriguing notion, far more menacing than any of us had ever imagined. After sex with Glenda, the camera fixes on a semi‑naked Caine, smoking a cigarette, and watching a poor quality pornography film shot on a hand held camera and projected across the windowless bedroom onto the white wall ahead of the bed. Hodges cleverly set the scene up with the wall to the back of Carter acting as a mirror whereby we see the movie in real time with Jack. When he notices his niece in the picture so do we, although, like him, we have to watch for a couple of minutes longer to be sure it really is Doreen.

At first he appears transfixed by the movie. Given Jack’s personal history that we have already lived through to that point, we are aware that pornography is well within the bounds of his interest and fear nothing of any narrative significance can come from this post‑coital scene. Yet, all of a sudden, we notice a crack appear on his stoic, focused face. Quite unbelievably, we see him shed tears, his piercing, cold blue eyes filled with emotion for the first time in the film, even including his own brother’s funeral, which he participated in as if he were a statue.

Still, though, we are unsure of the trigger for his melancholy. Only when Jack storms up to the bathroom, where Glenda is naked and submerged in water, demanding to know who the young schoolgirl in the movie is (we can clearly see Glenda as one of the other actresses in the projector film), do we begin to piece together the unthinkable. Pornography was not the multi‑million dollar industry that it is today and the audience would have found the realisation of Doreen’s plight a truly shocking revelation.

It would be no exaggeration to describe this particular scene as the crux of the entire film. Certainly, Mike Hodges thought as much. In the commentary to the digitally enhanced re‑release of the movie he explains how shooting the scene between Jack and Glenda was the most taught he had ever presided over; how Michael Caine psyched himself up for the scene so much that he lost control of his composure off camera. The scene reveals to the viewer the plot of the film, a necessarily pedantic moment before the action goes into over‑drive. “What did he (Caine) give me? He gave me the film in many ways. If he hadn’t made this scene work it would have been a horrible film.”12 It is true that viewer must feel the rage and underlying sadness of Jack Carter to have any engagement in the conclusion to the film. The audience must know the exact, simple reason behind Carter’s ensuing orgy of revenge‑fuelled violence. Caine makes it clear while holding the actress by the scruff of her sopping wet neck.

Carter to Glenda: “You didn’t know her last name?”

Glenda to Carter: “No.”

Carter to Glenda: “It’s Carter. That’s my name. And her father is my brother and he was murdered last Sunday.”

From this juncture on, the central character and plot of the movie accelerate their descent towards the intractable, inevitable conclusion.

At this point it is important to critically evaluate the central character of Jack Carter so as to define where exactly the film’s ultimate power resides. As we have already discussed, the audience establishes an early link with Carter and he is in almost every single shot of the final edit; Carter literally dominates the movie. We follow him on his quest for the perpetrators to his brother’s murder, involving a sub‑text of colourful underworld characters like Eric (Ian Hendry) and Con (George Sewell). We are struck by his callous and distant persona and his sarcastic nature, superbly evidenced in the second scene involving Jack and his niece, outside of a late night city centre diner.

Carter to Doreen: “How’s school?”

Doreen: “I left last year.”

Carter: “What are you doing now?”

Doreen: “Working in Woolworth’s.”

Carter: “That must be very interesting.”

That he is eccentric is likewise understood, typified when he walks stark naked down the street with a twelve bore shotgun outside of the house he is staying in. Furthermore, it is signalled that Jack is held in high esteem by his gangster associates and is clearly in possession of a coveted reputation as a tough man, underscored when the remarkably camp crime kingpin Kinnear (John Osborne) says to his mistress, “you don’t offer a man like Jack a drink in a piddly little glass like that; give him the bloody bottle.” It is all part of the building blocks that piece together to give us a wonderfully mosaic character, full of complexity and contradiction, including details such as Carter’s incessant pill‑taking and the curious nasal drops that he administers on his initial train ride north.

Hodges is right in pointing out that, had Michael Caine not been cast in the lead role with his inherent charisma and brilliantly subtle acting techniques, the film would have remained anchored in its ultimately negative depiction of humanity. Instead, Caine plays Jack Carter with an underlying degree of humanity, a small fragment of morality left within an otherwise deserted soul. What this means is that the audience is aware that Carter is aware that his is sick. We can see it when he is following Margaret through the winding, dark streets of Newcastle and in a more poignant scene towards the end of the film where Carter is sat on a ferry: in idolising the young family sat next to him we are made aware that this is a life that Carter can never lead, though we are left with the feeling that he wished he could have turned out in that socially acceptable way.

It is impossible to understate the significance of Caine’s subtle performance. The power of his acting is so strong that it even misleads us into believing that Get Carter is an essentially violent film. It is not. The scene, for instance, where Carter stabs Con at the back of the bookmakers, is non gratuitous. All of the anger, the menace and the rage of the scene are contained in Caine’s contorted face. It is in his features that we see an image of hell; the actual violence, in real terms, is minimal, especially by contemporary standards. It was also something of a risk for Michael Caine to take the role of Jack Carter in 1971, when he had only just begin to establish himself as a leading actor. Plenty of actors would have shied away from a script that demanded the lead character be mean, dispirited and violent; more still would have disliked the fact that Carter has to die in the end, a stumbling block for many leading Hollywood actors. It is not surprising that many fans believe Get Carter to be Michael Caine’s finest hour.

Get Carter is an important film in the study of the portrayal of women in Britain. It is immediately noticeable that all of the women in Get Carter are troubled, unstable and disempowered. Mirroring the paradox of Carter’s London swagger in the heart of industrial Newcastle, the treatment of women in Get Carter can be seen as a commentary on the anxieties of the time, especially concerning the consequences of the culture of permissive, promiscuous sexuality that had characterised the previous decade where films painted a distinctly different view of femininity and female sexuality.

“The narrative of these films (of the 60s) heralded a new feminine perspective marked by the importance of sexual expression to self identity; the centrality of individualised forms of glamour to a more female orientated public life, and London’s structural role in enabling and authorising this glamour and agency. Like the beauty and fashion spreads in women’s magazines, this glamour has a feminine address, foregrounding its role in the creation of a new and powerful self.”13

It is as if Hodges (himself from the South East of England) was determined to shatter the myths of British life with his first feature film. Outside of Swinging London, he seems to state existed a world where women have not yet achieved anything approaching parity with their male counterparts. Consider the characters. Glenda is a kept woman, pretty and voluptuous, yet she is weak and corruptible. Doreen (Petra Markham) has been taken advantage of and seems to have no future outside of her mundane job at Woolworth’s. Margaret (Dorothy White) is reviled as a scheming opportunist, but again she lacks power within her community and is at the mercy of the strong, villainous men around her. Even the landlady Edna (Rosemarie Dunham) with her own property and steady income is depicted as weak willed and corruptible. Despite her instincts about Carter she is still ultimately submissive and shares her bed with the gangster. The movie’s only female star, Britt Ekland, who plays Anna, is at the centre of a dangerous love triangle involving Carter and his boss; two scenes showing her mutilated face after her sexual indiscretions come to light were cut out of the final edit, much to the actresses’ chagrin.

All classic movies rely to some degree upon the musical score prepared for production. In Get Carter’s case, Roy Budd opted for a simple, almost child‑like central theme that rested on a few melancholic notes on a keyboard. Hodges cleverly introduces this score first at the beginning of the film, again in the middle when Carter disposes of Glenda’s body locked in the boot of her car, and finally at the final scene on the beach. In this sense, the music in Get Carter is used in an operatic manner, serving as book ends by which the viewer can chart their progress through the movie. Hodges likewise uses the haunting sound of a chilling wind at the same intervals, again to act as a pointer to important sections in the film.

The conclusion to the film remains truly shocking today. It was certainly unconventional in its time, but in light of the use of pornography and handguns in British crime (both rarities in 1971), the audience could view the end of the film in its true context. Once Carter has wreaked his revenge on all of the characters involved in Doreen’s sexual humiliation, he sets his sights on his nemesis, Eric. By this point, the villain has become the hero. In a distorted take on the knight in shining armour tale, Carter is exacting his terrible revenge for the sake of his niece’s honour. There is no mileage for him in the destruction of so many people upon whom he depends for a livelihood. As we are constantly reminded, Jack aims to flee to South America with Anna, which makes his insistence upon revenge all the more perplexing and perversely heroic.

After killing Eric by mimicking the way in which he disposed of Frank, Carter’s inherent madness comes rushing to the surface; his face cracks and he lets out a menacing cackle as Eric’s body is mechanically deposited into the sea. We are only surprised that he has not cracked sooner.

Justice is finally and ultimately served in the movie’s final scene. Aiming to throw his shotgun into the sea the sniper who is sat with Carter in the train carriage at the beginning of the film shoots him down. We are left unaware as to whether Carter had just retired from life as a hit man. Carter is left spread‑eagled on the dirty sand of the Newcastle beach, the waves crashing against his lifeless body. In terms of iconographic impact, this final scene packs a considerable punch; a fitting conclusion to a masterful portrayal of real life within the bounds of a revitalised traditional genre.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- J. Ashby & A. Higson (Edtd.), British Cinema: Past and Present (Routledge; London & New York, 2001)

- J. Boorman & W. Donohue (Edtd.), Projections 3: Film‑makers on Film‑making (Faber & Faber; London & Boston, 1994)

- D. Bordwell, Narration in the Fiction Film (Routledge; London, 1993)

- S. Chibnall & R. Murphy, The British Crime Film (Routledge; London, 1999)

- J. Ellis, Visible Fictions: Cinema: Television: Video (Routledge; London & New York, 1982)

- P. Gillett, The British Working Class in Post‑war Film (Manchester University Press; Manchester & New York, 2003)

- W. Hall, Arise Sir Michael Caine: the Autobiography (John Blake; London, 2000)

- R. Murphy (Edtd.), The British Cinema Book: Second Edition, (British Film Institute Publishing; London, 2001)

- J. Nelmes (Edtd.), An Introduction to Film Studies: Third Edition (Routledge; London & New York, 2000)

- J. Smith, Gangster Films (Virgin Books; London, 2004)

- Selected Articles

S. Chibnall, Travels in Ladland: The British Gangster Film Cycle, 1998‑2001, in, R. Murphy (Edtd.) The British Cinema Book: Second Edition, (British Film Institute Publishing; London, 2001) - P. Church Gibson & A. Hill, ‘Tutte e Marchio!’: Excess, Masquerade and Performativity in 70s Cinema, in, R. Murphy (Edtd.) The British Cinema Book: Second Edition, (British Film Institute Publishing; London, 2001)

- P. Hutchings, Beyond the New Wave: Realism in British Cinema, 1959‑63, in, R. Murphy (Edtd.) The British Cinema Book: Second Edition, (British Film Institute Publishing; London, 2001)

- M. Luckett, Travel and Mobility: Femininity and National Identity in Swinging London Films, in, J. Ashby & A. Higson (Edtd.), British Cinema: Past and Present (Routledge; London & New York, 2001)

- A. Sargeant, Marking out the Territory: Aspects of British Cinema, in, J. Nelmes (Edtd.), An Introduction to Film Studies: Third Edition (Routledge; London & New York, 2000)

- G. Van Sant, The Hollywood Way, in, J. Boorman & W. Donohue (Edtd.), Projections 3: Film‑makers on Film‑making (Faber & Faber; London & Boston, 1994)

Magazines

C. Upcher, The Mark of Caine, in, GQ Magazine (September, 1992)

Films

- Get Carter (M. Hodges; MGM Films, 1971)

Footnotes

- J. Smith, Gangster Films (Virgin Books; London, 2004), pp.113‑4

- C. Upcher, The Mark of Caine, in, GQ Magazine (September, 1992), pp. 103‑5

- G. Van Sant, The Hollywood Way, in, J. Boorman & W. Donohue (Edtd.), Projections 3: Film‑makers on Film‑making (Faber & Faber; London & Boston, 1994), p.214

- W. Hall, Arise Sir Michael Caine: the Autobiography (John Blake; London, 2000), pp.182‑3

- P. Gillett, The British Working Class in Post‑war Film (Manchester University Press; Manchester & New York, 2003), pp.116‑7

- J. Ellis, Visible Fictions: Cinema: Television: Video (Routledge; London & New York, 1982), p.38

- P. Church Gibson & A. Hill, ‘Tutte e Marchio!’: Excess, Masquerade and Performativity in 70s Cinema, in, R. Murphy (Edtd.) The British Cinema Book: Second Edition, (British Film Institute Publishing; London, 2001), p.264

- A. Sargeant, Marking out the Territory: Aspects of British Cinema, in, J. Nelmes (Edtd.), An Introduction to Film Studies: Third Edition (Routledge; London & New York, 2000), p.322

- P. Hutchings, Beyond the New Wave: Realism in British Cinema, 1959‑63, in, The British Cinema Book: Second Edition, p.146

- S. Chibnall, Travels in Ladland: The British Gangster Film Cycle, 1998‑2001, in, The British Cinema Book: Second Edition, p.282

- D. Bordwell, Narration in the Fiction Film (Routledge; London, 1993), p.65

- M. Hodges, quoted in, Commentary; Get Carter (MGM Films, 1971)

- M. Luckett, Travel and Mobility: Femininity and National Identity in Swinging London Films, in, J. Ashby & A. Higson (Edtd.), British Cinema: Past and Present (Routledge; London & New York, 2001), p.234